*This post contains spoilers*

A particularly interesting subgenre of horror that does not get the attention it deserves is films on films, or movies about movies. These movies often get lumped in with found footage and mockumentary style films, but there are a few key differences that make them categorically distinct and worthy of their own recognition. Found footage and mockumentary style films, or “POV horror”, incorporate the viewer into the story. We take on the perspective of the person holding the camera and are made to feel as though we are witnessing real events unfolding in real time. Part of the appeal is feeling like we’re watching something that we aren’t supposed to see, like a video recorded for someone else that made it into our hands by mistake. Notable examples of this would be The Blair Witch Project (1999), Cloverfield (2008), Rec (2007), Creep (2014), and Paranormal Activity (2007). Films on films don’t try to play with our perception in the same way. The fourth wall remains firmly in place and we can experience the film from a safe distance. Yet there’s a sense of discomfort that occurs when horror movies pull back the curtain and allow us to take a good, long look. To an extent, this also feels like we’re watching something that we aren’t supposed to see.

One of my favorite examples of this is Peter Strickland’s Berberian Sound Studio (2012). The main character, Gilderoy, is a sound engineer who gets duped into working on giallo-style film in Italy called The Equestrian Vortex. Having never worked on a horror film before, Gilderoy becomes increasingly more disturbed by the violence in the film and the lines between his work and reality become… blurred. A lot of the film is spent highlighting the technical aspects of sound mixing, even when we start to experience Gilderoy’s fractured reality. The way the movie utilizes sound acts as both a premise and the primary source of tension throughout the film. Extended scenes of foley artists using produce to create gruesome sound effects serve as a constant reminder to us that this isn’t real, but as Gilderoy’s experience becomes increasingly more distorted, things begin to feel jumbled for the viewer too. If we know this isn’t real, why do we still feel so uneasy? That unease is the film’s greatest strength and most impressive trick. Even though we are watching Gilderoy and his crew smashing watermelons and ripping cabbage to produce sound effects, our brains still register the squelching and tearing sounds as violence and gore. Strickland leans into this tension, showing how easily fear and perception can override logic and rational understanding. Strickland provides the sound and lets our brains fill in the rest.

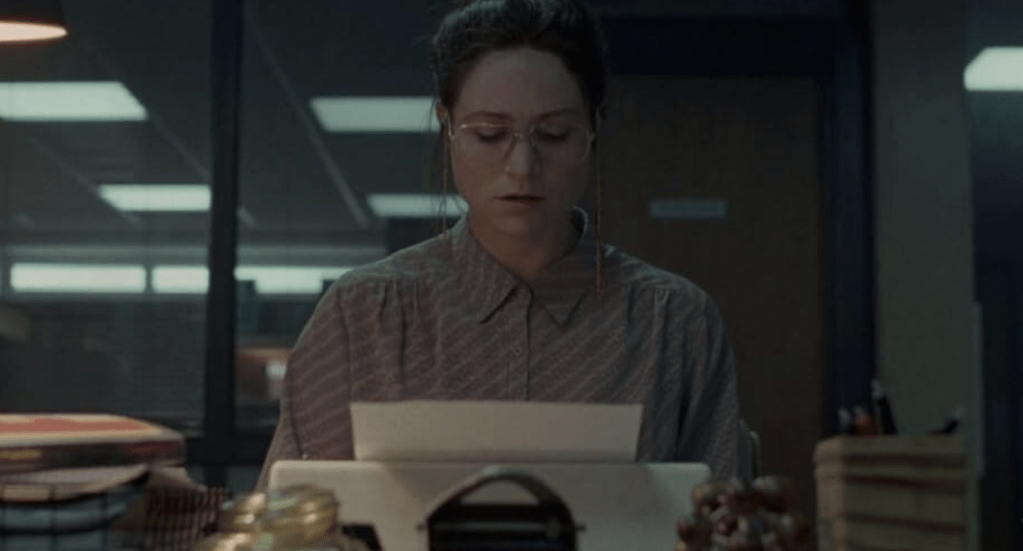

Another standout example is Prano Bailey-Bond’s debut feature Censor (2021). The film follows Enid, a dedicated employee of the British Board of Film Classification who works as a censor editing the nastiness out of video nasties. Enid takes her job very seriously and views herself as a kind of moral gatekeeper who protects the public from the harmful effects of violence on the screen. In the midst of an extremely stressful work situation, Enid screens a film that, for reasons not yet known to the viewers, hits a bit too close to home and she begins to unravel. As the story progresses, we learn that Enid is carrying unresolved trauma from the disappearance of her sister when they were children and her strict policing of fictional violence had been her way of compensating for her inability to protect her sister from real-world harm. What makes Censor so impactful is how it blurs the boundaries between Enid’s work and her trauma, with the two becoming practically indistinguishable. As her mental state deteriorates, she finds herself living out scenarios that replicate scenes she once censored. This forces us, the viewers, to witness the exact content that Enid tried to shield us from. It’s a never ending cycle of art imitating life imitating art imitating life. In the film’s final moments, Enid has fully surrendered to her delusions. In her new technicolor reality, she rescues her sister, reunites her family, and has successfully banned violent movies entirely, which has, in turn, put a stop to all crime. But in the final scene, reality jitters through and we see flashes of the horrors that have actually occurred. This upsetting final scene invites us to consider the relationship between perception and reality. Maybe there are some things we don’t need to see, but just because we can’t see them doesn’t mean that they aren’t actually there.

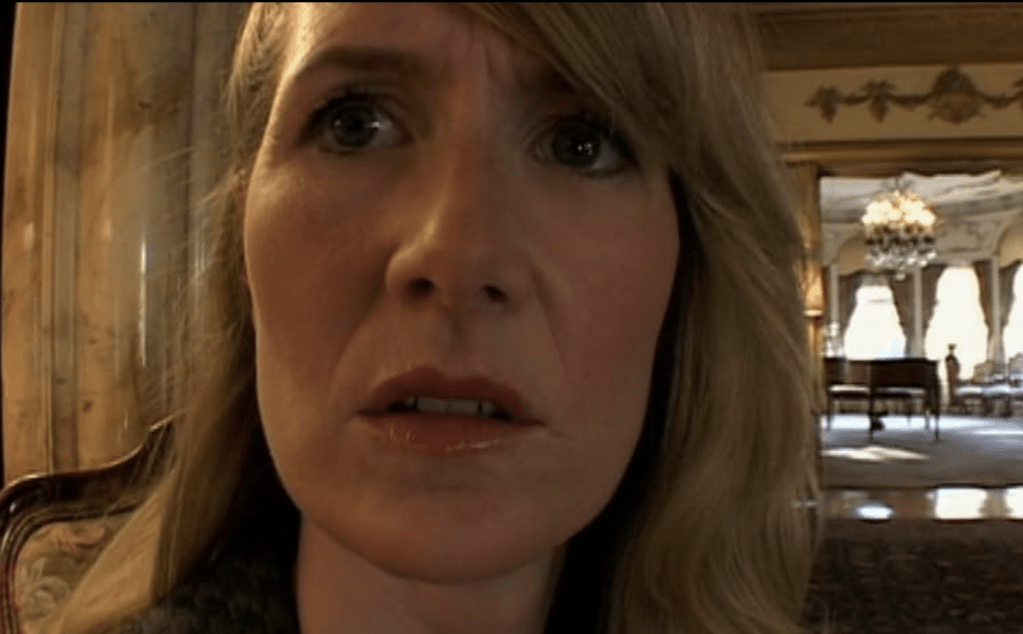

David Lynch’s absolute fever dream Inland Empire (2006) might be the clearest and most unsettling example of how films on films can play with perception. In true David Lynch fashion, it is never really clear what is going on at any given moment and that’s precisely what makes Inland Empire so creepy. The main character, Nikki, is an actress working on a remake of a film purported to be cursed. As Nikki spends more time in character the story becomes increasingly convoluted and any semblance of a narrative that may have existed goes out the window. Timelines become fractured, character identities shift, and dialogue is recycled over and over again throughout different scenes. This results in a sense of extreme disorientation for Nikki and for us as viewers. The surreal imagery and lack of cohesion between scenes give the movie a threatening vibe even if you can’t quite articulate why. The inability to make sense of the narrative of Inland Empire as you’re watching creates an uncanny experience. There are bits of narrative scattered throughout and your brain tries to piece something together, but the inability to make sense of it all creates a feeling of agitation that never quite resolves. It becomes impossible to distinguish which scenes are real, which scenes are Nikki playing a role, and which scenes are something else entirely.

Not all films on films play with perception to this degree. I love the trippy, meta quality of films on films that rely on psychological horror to make the movie impactful, but sometimes you don’t want to have to think so hard. The more straightforward films on films tend to take a more traditional slasher route. These are films like X (2022), Knife + Heart (2018), and Scream 3 (2000). These films all share a similar premise: 1) someone is making a movie. 2) Someone else is unhappy about it. 3) That someone else chooses to express their disapproval with murder. There are deeper, more nuanced elements to each of these films, but you can still enjoy them if you don’t feel like dissecting the symbolism of certain imagery or the cultural narratives woven into the dialogue. Overall, films on films is a horror subgenre that I am always happy to come across. There are countless other great examples of these types of films and I look forward to seeing how this subgenre continues to evolve.

Leave a comment